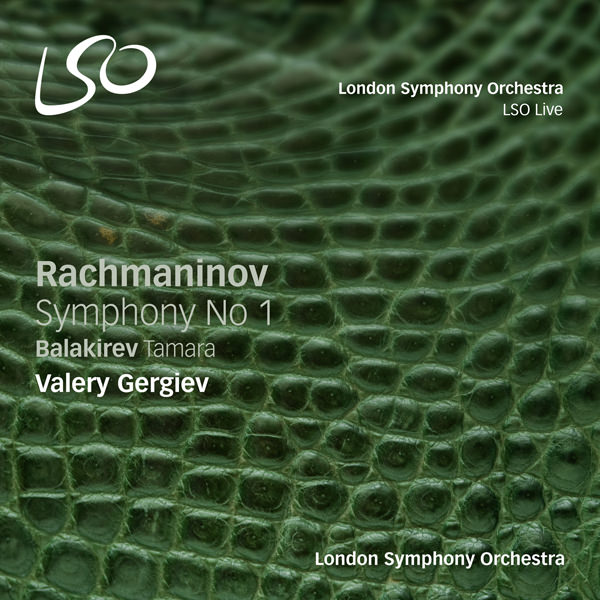

Sergei Rachmaninov – Symphony No. 1 / Mily Balakirev – Tamara – London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev (2016)

DSF Stereo DSD64/2.82MHz | Time – 01:01:22 minutes | 2,31 GB | Genre: Classical

Studio Masters, Official Digital Download – Source: nativeDSDmusic | Digital Booklet | © LSO

Recorded live in DSD 128fs, 19 February 2015 at the Barbican, London

Symphony No 1 in D minor Op 13 :: Rachmaninov’s star shone brightly at the beginning of his career. He was barely twenty when his oneact opera Aleko, composed as a graduation exercise from the Moscow Conservatory, was praised by Tchaikovsky and performed at the Bolshoi. He had also already composed his First Piano Concerto. Following two smaller-scale orchestral pieces, The Rock and the Fantasy on Gypsy Themes, he felt ready to tackle the most demanding orchestral form. He devoted most of 1895 to composing his enormously ambitious First Symphony, a work that would surpass everything he had yet achieved. ‘I believed I had opened up entirely new paths’, he recalled many years later.

The work was accepted for performance by Belyayev, founder and patron of the Russian Symphony Concerts in St Petersburg, a series devoted to the promotion of new Russian music under the joint direction of Rimsky-Korsakov and Glazunov. Perhaps Rachmaninov would have done better to get his symphony performed in Moscow, where he was better known, but he was no doubt pleased at the thought of a prestigious first performance in St Petersburg, where Glazunov had already conducted a performance of The Rock. The symphony, however, was another matter: both Rimsky-Korsakov and Glazunov expressed doubts about it, and although Glazunov was a fine composer and all-round musician, he was not an inspiring conductor, and certainly not the man to bring out the best in music which he didn’t particularly like. The symphony’s rehearsals were completely inadequate (there were two other first performances also on the programme) and the performance on 27 March 1897 is one of music’s most notorious disasters. Rachmaninov cowered outside the hall, barely able to recognise his own music. As always happens when a new work fails, the composer gets all the blame, rather than the conductor (who, other failings aside, may have been drunk). Most reviews were scathing. Rachmaninov’s self confidence was shattered and he was unable to compose any important new work until the Second Piano Concerto in 1901 (though he was very active in other fields during this period, when he laid the foundations for his career as a pianist and conductor).

At various times Rachmaninov thought of revising the symphony, but when he emigrated in 1918 the score was left behind in Russia and subsequently disappeared. It was only in 1944 that the original orchestral parts were rediscovered, allowing the symphony to be reconstructed and performed in Moscow on 17 October 1945. Two things became clear when the symphony was brought back to life: that this was the boldest and most interesting Russian symphony in the decade after Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique, and that its hostile reception changed the course of Rachmaninov’s composition, for he never again allowed himself the expression of such raw passion and such blatantly tragic gestures.

Like Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov creates drama by contrasting thematic groups of very different character, but the unity of the symphony is ensured by a cyclic form and thematic cross-references that are always clearly audible. Each movement begins with the same four-note figure. In the first movement it is followed immediately by an ominous descending figure in the lower strings. This is the symphony’s recurrent motto theme, which in various transformations is heard in many of the subsequent themes.

Throughout the symphony there is a striking contrast between themes of an almost liturgical character and themes with the inflections of gypsy music. This polarity has been interpreted as the reflection of a personal drama in Rachmaninov’s life. The score has a dedication ‘To A.L.’ and the grim inscription from St Paul, ‘Vengeance is mine, I shall repay’. This is also the epigraph to Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, the story of a passionate woman driven to destruction. ‘A.L.’ is almost certainly Anna Lodïzhenskaya, the part-gypsy wife of a friend; but nothing certain is known about Rachmaninov’s relations with her, and their story is still shrouded in mystery. What we do know is that in his last work, the Symphonic Dances, Rachmaninov recalled the motto theme of his First Symphony in a golden shimmer of sound: whatever experience lay behind the symphony, it was still very much present in Rachmaninov’s mind at the end of his life.

Tamara :: Balakirev first visited the Caucasus in 1862 and was thrilled by the dramatic landscapes, the people and their music. One result of this visit was Islamey, the fiendishly difficult ‘oriental fantasy’ for piano that he composed in autumn of 1869. Then came Tamara, the symphonic poem eventually completed only in 1882, and which is often considered his masterpiece.

Tamara takes its title from a poem by Mikhail Lermontov (1814-41) describing a deep gorge in northern Georgia through which flows the river Terek. Overlooking the gorge is a high tower in which lives the princess Tamara, ‘as beautiful as a heavenly angel, as evil and cunning as a demon’. A passing traveller is drawn to this tower as if by a spell, and is there welcomed by Tamara, dressed in brocade and pearls and lying on a soft couch. ‘Strange, wild sounds echoed throughout the night’, and it seemed that within Tamara’s tower ‘a hundred passionate youths and girls had come together on their wedding night to the sounds of wailing at a sumptuous funeral’. But as the first light of dawn comes over the mountains, an eerie silence falls. The river rushes on, seeming to weep as a corpse is carried along by its waters. From a window of the tower there is a flutter of white and a whispered farewell, ‘such a tender farewell, the voice was so sweet, it seemed to promise an ecstatic meeting, a loving caress’.

The oriental style pioneered by Glinka in his opera Ruslan and Lyudmila, and then developed to a high level by Balakirev and his followers, featured two main elements: a sinuous type of slow melody, often heavily ornamented and with augmented intervals, and fast dance measures with much repetition, often accompanied by lavish percussion. In Tamara these features are essential to illustrating the atmosphere and narrative course of the poem. The opening is nature painting, evoking the river gorge; from this there gradually emerges the first of Tamara’s themes on rising woodwind. There is a feeling of gathering doom as further themes add detail and colour to the narrative. The syncopations and rhythmic dislocations, the sheer frenzy, even hysteria, of some passages, are as disturbing as they are exciting. -Andrew Huth © 2016

Tracklist:

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943)

Symphony No 1 in D minor, Op 13 (1895)

1. I. Grave – Allegro ma non troppo 13:35

2. II. Allegro animato 07:03

3. III. Larghetto 09:24

4. IV. Allegro con fuoco 11:44

Mily Balakirev (1837-1910)

5. Tamara (1867-1882) 19:36

Personnel:

London Symphony Orchestra

Valery Gergiev, conductor

DSF DSD64/2.82MHz

mqs.link_RachmaninvSymphnyN.1BalakirevTamaraLSValeryGergiev2016HRADSD64.part1.rar

mqs.link_RachmaninvSymphnyN.1BalakirevTamaraLSValeryGergiev2016HRADSD64.part2.rar

mqs.link_RachmaninvSymphnyN.1BalakirevTamaraLSValeryGergiev2016HRADSD64.part3.rar

FLAC 24bit/96kHz

mqs.link_RachmaninvSymphnyN.1BalakirevTamaraLSValeryGergiev2016hyperin2496.part1.rar

mqs.link_RachmaninvSymphnyN.1BalakirevTamaraLSValeryGergiev2016hyperin2496.part2.rar

![Carl Nielsen - Symphonies Nos. 1-6 - London Symphony Orchestra, Sir Colin Davis (2015) [Blu-Ray Pure Audio Disc + DSF Stereo DSD64/2.82MHz] Carl Nielsen - Symphonies Nos. 1-6 - London Symphony Orchestra, Sir Colin Davis (2015) [Blu-Ray Pure Audio Disc + DSF Stereo DSD64/2.82MHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2015/09/Wnf48VE.jpg)

![Itzhak Perlman - The Complete Warner Recordings 1972-1980 (2015) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz] Itzhak Perlman - The Complete Warner Recordings 1972-1980 (2015) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2019/12/IpmBmeR.jpg)

![London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov: Symphony No. 3; Balakirev: Russia (2015) [nativeDSDmusic DSF DSD64/2.82MHz] London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov: Symphony No. 3; Balakirev: Russia (2015) [nativeDSDmusic DSF DSD64/2.82MHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2019/05/BSou4Lj.jpg)

![Maria Callas - Remastered The Complete Studio Recordings 1949-1969 (2014) [Qobuz FLAC 24bit/96kHz] Maria Callas - Remastered The Complete Studio Recordings 1949-1969 (2014) [Qobuz FLAC 24bit/96kHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2018/12/Vw7IHlv-1.jpg)

![Sergei Rachmaninov: Symphony No 3 / Mily Balakirev: Russia - London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev (2015) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz] Sergei Rachmaninov: Symphony No 3 / Mily Balakirev: Russia - London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev (2015) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2016/05/3MBnI0P.jpg)

![Glenn Gould - The Complete Columbia Album Collection (2015 Remastered Edition) [Qobuz FLAC 24bit/44,1kHz] Glenn Gould - The Complete Columbia Album Collection (2015 Remastered Edition) [Qobuz FLAC 24bit/44,1kHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2017/07/2bHwfbA.jpg)

![Zuzana Ruzickova - J.S. Bach: The Complete Keyboard Works (2016) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz] Zuzana Ruzickova - J.S. Bach: The Complete Keyboard Works (2016) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2018/09/r94XYtX.jpg)

![London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov: Symphonic Dances; Stravinsky: Symphony in Three Movements (2012) [nativeDSDmusic DSF DSD64/2.82MHz] London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov: Symphonic Dances; Stravinsky: Symphony in Three Movements (2012) [nativeDSDmusic DSF DSD64/2.82MHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2019/05/uY4KEqQ.jpg)

![Valery Gergiev - Sommernachtskonzert 2020/Summer Night Concert 2020 (2020) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz] Valery Gergiev - Sommernachtskonzert 2020/Summer Night Concert 2020 (2020) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2020/12/ssQGLxM.jpg)

![Valery Gergiev, London Symphony Orchestra - Mahler : Symphony No. 7 (2020) [FLAC 24bit/44,1kHz] Valery Gergiev, London Symphony Orchestra - Mahler : Symphony No. 7 (2020) [FLAC 24bit/44,1kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2022/09/20/ts4ocld3dgsvb_600.jpg)

![London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Tchaikovsky: Symphonies Nos. 1-3 (2012) [nativeDSDmusic DSF DSD64/2.82MHz] London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Tchaikovsky: Symphonies Nos. 1-3 (2012) [nativeDSDmusic DSF DSD64/2.82MHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2019/05/5oqqXRM.jpg)

![Leonore Piano Trio - Arensky: Piano Trios (2014) [Hyperion FLAC 24bit/96kHz] Leonore Piano Trio - Arensky: Piano Trios (2014) [Hyperion FLAC 24bit/96kHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2017/08/5QaV7KV.jpg)

![London Symphony Orchestra & Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov: Symphonies Nos. 1-3 - Symphonic Dances (2018) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz] London Symphony Orchestra & Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov: Symphonies Nos. 1-3 - Symphonic Dances (2018) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2018/10/oEb1W8L.jpg)

![London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov: Symphony No1 and Balakirev Tamara (2016) [Qobuz FLAC 24bit/96kHz] London Symphony Orchestra, Valery Gergiev - Rachmaninov: Symphony No1 and Balakirev Tamara (2016) [Qobuz FLAC 24bit/96kHz]](https://getimg.link/images/imgimgimg/uploads/2017/09/lLjzwkf.jpg)